Looking back on 9/11 two decades after the tragedy.

By Andrea Dawn Clark

Twenty years ago on September 11, 2001, nearly 3,000 lives were cruelly taken away from their family, friends, and colleagues. They senselessly lost fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, and even young children at the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan, the Pentagon, and a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. As a New York City college focused on educating firefighters, law enforcement officers, and emergency medical professionals, the toll on our community was steep—John Jay lost 67 heroes that day. These brave men and women made the ultimate sacrifice to save others in need. Now, after two decades, the emotional, psychological, and physical pain of that tragic day still runs deep. First responders and civilians continue to face life-threatening diseases because of the toxic air they inhaled; while many others have died because of the exposure to deadly dust and debris. As a community committed to public service, we honor the legacy of our fallen heroes, and we strive to ensure that a tragedy like 9/11 never happens again.

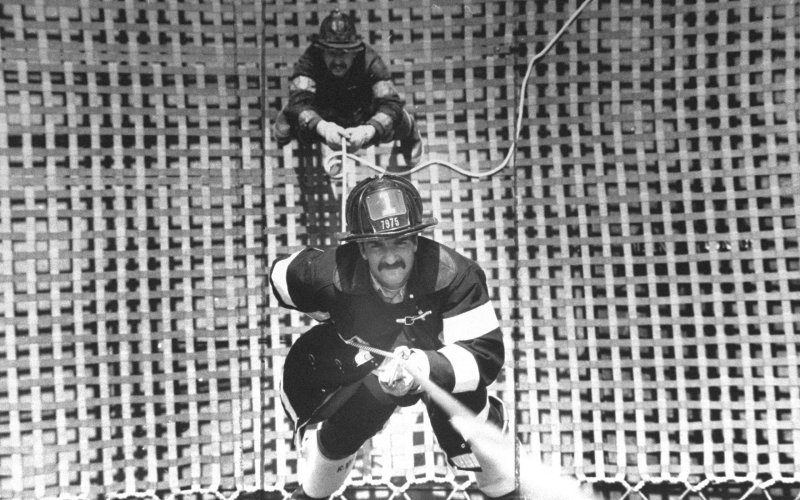

Ronald P. Bucca, FDNY Fire Marshal

Throughout his career, New York City Fire Department (FDNY) Fire Marshal Ronald P. Bucca dedicated his life to helping others and serving his country. “He was in the Army as a helicopter mechanic. After Vietnam he went into the Army Reserves, and then he got into the FDNY fulltime,” says his son, also named Ronald “Ron” Bucca. “As he progressed within the fire department, he wanted to learn more about fire science and being a better professional. When he became a Fire Marshal in the FDNY, he was tasked with investigating arsons and the origin of fires. At John Jay, he studied fire science, terrorism, and criminal justice. The school really offered him an abundance of resources.” Bucca grew up in Queens, New York, but since he worked in Manhattan, he’d often walk his son through John Jay’s campus and tell him about the College.

The Family Man

Despite the fact that Bucca was juggling a lot of different hats—a father of two, a husband of 23 years, a Warrant Officer in the Army Reserve, and an FDNY Fire Marshal—he was always there for his family. “He was a great father. He was always at baseball games. He was always involved in me and my sister’s lives,” says his son. “Looking back at that time, what sticks out the most to me is his mentorship. He always wanted to teach me what he knew.” Whether Bucca took his kids camping or on a trip to a museum—he was an avid historian—the seasoned Fire Marshal wanted to create learning experiences for his children. “That’s what I hold onto the most. He had so many facets to his life. In retrospect, you just wish you had those extra years, or even minutes, to ask more questions. But, I’m certainly grateful for the time I had with him and the knowledge that he did share with me.”

The Night Before

Like so many parents with older children, at the end of August 2001, Bucca dropped off his son at college. He helped move in his son’s belongings, explored the sites in New Orleans, and then headed back to New York City. “The night before 9/11, I talked to my father like any other college kid. We were trying to work out the money for the flight home for Thanksgiving,” says his son. “It was just a normal conversation. ‘I love you. Talk soon.’ Then, the next morning I woke up for classes and saw what was happening on television.” Young Ron tried to get a hold of his mother, but because she was a nurse, she was busy setting up a triage unit. He tried calling his father, but there was no answer. He finally got in touch with his grandmother who informed him that his father was in fact at the site. “And then, like the rest of the world, we waited. There was no flow of information for hours. Then at about 10 o’clock that night, I got a call from the Chief Fire Marshal saying, ‘Hey, we haven’t heard from your dad yet. You may want to come home.’” Since there were no available flights, Bucca’s son and his roommates hopped in a car and drove from Louisiana to New York. After connecting with one of the other Fire Marshals that his father worked with, he went down to the site himself. “I wanted to start looking for him right away. If anybody was going to find my dad, it was going to be me.”

The 78th Floor

Before September 11, Fire Marshal Bucca investigated the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. “My dad had an intricate knowledge of the towers themselves. In fact, the month before, he talked to the guys in maintenance about an evacuation plan,” says his son. “He knew the stairwells. He knew the layout of the building. He knew about terrorist organizations like Al Qaeda, and he knew who Bin Laden and Ramzi Yousef were. There were only a few people who could connect all of the dots and my dad was one of them.”

Bucca’s base was in downtown Manhattan on Lafayette Street. When he showed up for work that day, the first plane had just flown into the North Tower. He immediately spoke to his supervisor and together they shot over to the buildings. Just as they were parking, the South Tower was hit. The two men navigated their way through the lobby toward a stairwell that would give them a direct path to the upper floors. On route, his supervisor saw a woman who was badly burnt and incapacitated; so, he helped her out of the building. Bucca continued upward toward the 78th floor of the South Tower. Through radio transmissions and eyewitness accounts, his son has been able to piece together his father’s final moments. “They were trying to put more water on the fire and my dad was providing first aid to the people who had been injured. All that training and all that education, everything culminated in this one moment in his life,” his son says, wiping tears from his eyes. “I obviously wish I had more time with him, but I truly believe he was where he was supposed to be, doing what he loved. Like all firefighters, I think he wanted to get to the point of impact to start trying to put out the fire—no matter how insurmountable that may have been. Later, they found him in like a pocket [of space] by a stairwell. His coat was on a lady he was trying to save.”

The Legacy

FDNY Fire Marshal Ronald P. Bucca was only 47 years old when he died in the South Tower while trying to save lives. “At the time, I thought he was old, but now that I’m coming to that age, I realize he was really young,” says his son. “He did a lot in his life, but there’s a lot more that he certainly could have done. He had one goal, helping people. That was always the goal.” After his father’s death, Ron finished his undergraduate degree and started a career in finance. “After reflecting on my father’s life and the impact that he was able to make on people, I started looking toward a life of service. I really wanted to protect my family and the rest of the nation. To kind of walk in his shoes, I wound up enlisting in late 2002 and becoming a Green Beret in the Army.” It was Ron’s way of creating a shared experience and putting the lessons from his father to good use.

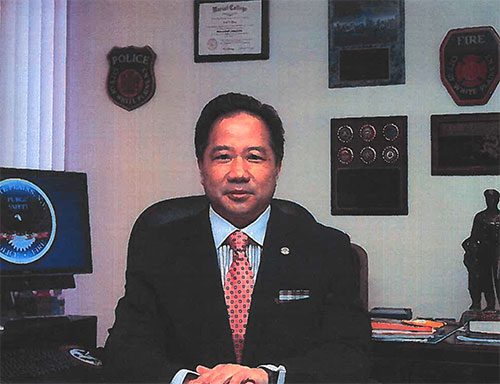

David Chong ’80, Retired NYPD Commander

Growing up on the Lower East Side in Chinatown, New York, alumnus David Chong ’80 never really thought about the police. “Except to avoid them,” he says with a laugh. “I lived in a housing development with my mother. The only interactions I had with the police was when they would chase us away from hanging out in groups.” After his family relocated to Queens, New York, discos went into full swing and Chong worked security at one of the trendy discotheques. “It was during that ‘Son of Sam’ period and it was really kind of a tumultuous time,” says the current White Plains Safety Commissioner, who has over 22 years of New York City Police Department (NYPD) service under his belt. One day, after cleaning up the disco in the wee hours of the morning, Chong and some friends went to Jones Beach. As the sun started to rise, his friend’s father—who happened to be an NYPD police officer—told the young men that the “PD” was hiring. He instructed them to go to a public school in Greenwich Village, pay $5, show their driver’s licenses, and take the police exam. “We kidded with him and said, ‘Who wants to pay $5 to take an exam?’” says Chong. Nevertheless, he took the exam and aced it. “I didn’t see very many Asian-Americans taking the exam, but about three months later, I got a card from the Department saying that I passed. I actually scored 100 on the exam.”

The Education

After Chong passed the civil service exam, the idea of becoming a police officer became more real. “I didn’t know anything about policing, so I started to ask around and everyone said, ‘If you want to be a police officer, you should go to John Jay College.’” Once he earned an associate degree from Queensborough Community College, Chong enrolled at John Jay and was determined to get his bachelor’s degree in Criminal Justice. As he was taking classes, he steadily moved through the background investigation needed to join the NYPD. “They offered me the job in 1979, but I deferred because I had one semester left at John Jay. In 1980, I graduated and joined the NYPD,” he says. Since he looked younger, Chong immediately went undercover in the Flying Dragons gang. “After a couple of years, we took down a big gang investigation and I went to the police academy, which led me to a really good career with 22 and a half years with the NYPD.”

The Day of the Attack

In 2001, Chong graduated from the FBI National Academy and was serving as a Lieutenant in the Organized Crime Investigations Division. “On September 11th, I had to go downtown to the CCRB [Civilian Complaint Review Board], which was located at 40 Rector Street and was basically right beside the North Tower of the World Trade Center on West Street,” Chong recalls. “I remember that it was a beautiful, sunny morning. As I was driving down the FDR Drive, headed toward the Towers, I was looking at the horizon. The Twin Towers were always a part of the New York City skyline. I couldn’t remember the City without them.”

On his way into the building, he grabbed a copy of the New York Post. “I remember reading some kind of gossip about Mick Jagger’s daughter. Then I heard this tremendous boom and the entire building at 40 Rector Street shook.” Everybody at the CCRB started running around and panicking. A young woman came up to Chong and informed him that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. The thought seemed absurd to him. How could a plane hit the World Trade Center? Maybe it was a little passenger jet that lost its course? He thought to himself. “To my shock and absolute dismay, when I exited on Rector Street, I saw that it was a major airline that hit the North Tower. I saw part of the plane on West Street. I felt the heat and it was just raining down debris. I started to see body parts, and being a detective, the first thing on my mind was to look for a pen to mark the human body parts,” says Chong, shaking his head in disbelief of what he witnessed. He saw massive amounts of people standing around, looking up, frozen in complete shock. “I remember it being so surreal. People were jumping to their death from such a high place. I remember seeing one body bounce against a building and just break into pieces.”

Amidst absolute pandemonium, Chong knew he had to get civilians away from the scene. “As I made my way to the North Tower, I was screaming at people to run. I was yelling, ‘Run north! Run away from the Towers!’” When he got to the North Tower, security was advising people to go to the South Tower, which was not hit at the time and was where they were setting up a triage area. In his suit and tie, with his badge pinned to his jacket, Chong ran into the South Tower. “I remember hearing over a police radio that another airplane was coming in. I looked up into the sky and I saw an airliner swim inside the South Tower. I thought it was a nightmare.”

As a first responder, you’re trained not to take an elevator when something is burning. Chong saw an officer carrying two oxygen tanks and heading for the stairwell. “I said, ‘Give me a tank and I will come upstairs with you. He handed off a tank and we made it up between the 11th and 12th floors. What I remember the most is the smells. Smells of the burning building, smells of jet fuel, smells of burning flesh, all the smells that I still smell at nighttime in my sleep.” His senses of smell and sight intensified in the chaos; while his hearing muffled down to a low hum of sirens and screaming.

He saw two exhausted men bringing down a woman who was very badly burned. All three of them were covered in blood. “I remember saying to a young firefighter behind me, ‘Go over there and help these people.’ He said, ‘I don’t know who you are, but you can’t take me away from my group. I’m in full rescue equipment. You’re in a suit and tie. I think it’s better that you help them out.’” The young fireman’s logic made sense to Chong and he watched as the fireman climbed up the stairwell. After he took the hurt woman from the arms of the two men, he instructed them to get out of the building as fast as they could.

Chong tried to administer oxygen to the injured woman, but panic set in and he couldn’t get the tank to work. “I remember she was speaking Spanish to me and talking about her niños, which were her children. I told her, ‘Stay with me. We’re going to go downstairs. The ambulances are downstairs and you’re going to see your children once we get to the ambulances.’” As he helped her down the stairs and they stumbled through the lobby, he took off his suit jacket and covered her exposed body. Chong looked out onto Church Street and saw the flashing lights. We just have to make it to those flashing lights, he thought to himself. She’ll be okay if we make it to the flashing lights. “As we were walking, the floor opened up like a sinkhole. I lost my grip of her. Never saw her again,” says Chong, visibly still shaken from the experience.

The Rescue

As the building collapsed, Chong fell in between two concrete barriers that most likely saved his life. Two officers from the NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit walked by and saw his arm frantically pushing against the ground. Chong could hardly breathe. The air was thick, and his nose and mouth were filled with dirt and blood. “I was hurting so bad, but the adrenaline was going so heavy. I was trying my best, reaching, and hoping that she was beside me, but I couldn’t feel anything,” says Chong. Until they saw the gun on his belt, the Emergency Service officers who pulled him out of that concrete cocoon had no idea that he was also NYPD. Chong’s badge was on his jacket, and his jacket was wrapped around the badly burned woman. He implored the officers to help him find the woman. “I was just crawling on my hands and knees through the rubble looking for this woman. Then one of them said. ‘We have to go. We are getting a warning that the other tower is going to collapse.’” The two officers dragged Chong across Broadway by his armpits and dove into the Century 21 department store. The windows had all been blown out. Clothing, racks, and countertops were strewn across the floor. The two officers protectively covered Chong’s body with their bodies, and as the second Tower came down, a gush of wind and thunderous noise filled the air.

The Trauma

In 20 years, a day hasn’t gone by without Chong remembering the woman he lost in the lobby of the South Tower, the young fireman he watched go up the stairs, or the horrific sights and smells that arrested his senses. He lives his life battling Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and cancer. “I have survivor’s guilt. I don’t know why I ended up between those two concrete barriers,” he says. “The terror of that day has affected me forever.”

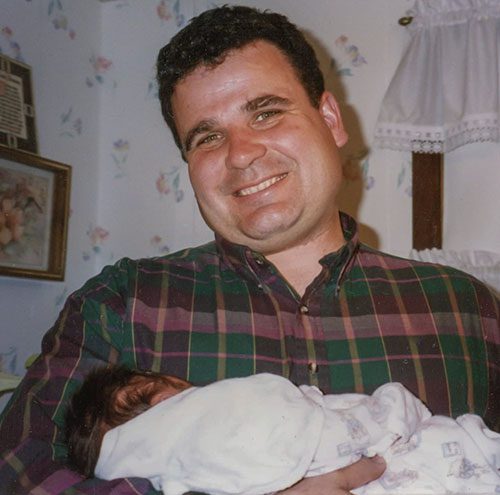

John Coughlin, NYPD Sergeant

In 2012, Erin Coughlin found the best way she could to honor her late father, New York City Police Department (NYPD) Sergeant John Coughlin. After graduating from the Police Academy and becoming an NYPD police officer herself, she put on a badge inscribed with her father’s shield number. Before September 11, 2001, Sergeant Coughlin was taking classes at John Jay College, working in the NYPD Emergency Services Unit, and finding precious time to be with his wife and three daughters. “He was just this big teddy bear of a human being,” says Erin, the oldest of the three girls, about her six-foot-two dad. “He was so much fun and he loved his little girls.”

The Girl Dad

Whenever Sergeant Coughlin had some time off, he made a point of spending it with his family. “He was always just there, always fun, and he loved us to death. He told us every chance he could get that he loved us,” says Erin. For the Coughlin girls, their dad’s precinct was almost an extension of their own home. “We’d go upstairs and eat in the kitchen. We’d go and see his big truck. We’d play in the nearby playgrounds,” she remembers. “And, when it was career day at school, he’d always come in with all this cool NYPD stuff.” It was important to Sergeant Coughlin that his daughters be proud of the work he did—and they always were.

In an effort to cool off in the summertime and spend some outdoor time together, the Coughlin family annually made their way up to Lake George for a week. “We weren’t rich by any means, but my parents made sacrifices to make sure that we had such a good childhood,” says Erin. Normally, the family would stay in a modest cabin, but in the summer of 2001, Sergeant Coughlin got to experience something he always wished for his family. “He dreamed of staying at a lakefront resort with a pool. Ironically, on our last trip with him, we were on the lake with a pool. God knows how much overtime he had to do to get us that place, but even in the moment we knew it was exciting and we appreciated it. We just didn’t know how important that trip would be.”

The News

On September 11, 2001, Erin was only 16 years old, and her sisters were 13 and six. Their father had to head to work extra early that day, so they didn’t get the chance to say goodbye to him that morning. It was Erin’s second week as a junior in high school, and during her third-period math class, an announcement came over the loudspeaker. The principal explained that there had been a plane crash at the World Trade Center. “I was looking out the window at the time, and I had this weird feeling even before the announcement came on. I had a gut feeling that something was wrong,” she says. “I knew he’d be down there because that’s what his unit did. They rescued people. None of us knew how serious it was at the time.”

A lot of her school friends had parents in the NYPD and the FDNY, and on September 11th, most of those students got picked up from school early. But because her mother was a nurse, Erin knew that wouldn’t be the case for her. “When I got to my sixth-period chemistry class, my teacher announced that the buildings had crashed down, and they didn’t know if anyone made it out.”

Erin made her way home from school that day and the phone was ringing off the hook. Everybody was wondering if her father was okay. Her aunt came over to comfort the girls and they anxiously watched the news coverage of the attack. When Erin’s mother finally made it home, it was 10 o’clock at night, and she was exhausted from both work and worry. Then a call came through and Mrs. Coughlin was informed that her husband was officially listed as “missing.”

The Final Moments

Sergeant Coughlin’s last radio transmission stated that his unit was on the 20th floor of the South Tower. “They grabbed all the stuff off the truck that day and they went in—ropes, harnesses, the whole bit. They just wanted to get people down the staircases as fast as they could,” says Erin. In the midst of the chaos, Sergeant Coughlin ran into an old high school friend. This friend actually made it out of the building and relayed his experience to Mrs. Coughlin. “He told my mother, ‘I saw him. He looked me in the eye and he said get out and run.’ I think that they all knew it was going to be bad. A few of the guys even found a way to quickly call home.”

The Message

Even after 20 years, the memory of that agonizing time—the waiting, the uncertainty, the unbearable feeling of loss—still pains NYPD police officer Erin Coughlin. Thinking back to her father—a John Jay student and avowed history buff—she wants the next generation of public safety leaders to always remember one thing: the humanity of those we lost. “When they went into those buildings that day, they were grabbing people and helping them run away. It didn’t matter what they looked like, what they believed in, what political party they were in, or anything like that. They just knew that there were thousands of people in that building who had heartbeats,” says Erin. “They just knew that the building was chockfull of humanity—from the dishwashers, to the window washers, to CEOs, business people, and people visiting. There were people in those buildings and other human beings went in to get them out.”